Low-income countries face fewer debt challenges today than they did 25 years ago, thanks in particular to the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative, which slashed unmanageable debt burdens across sub-Saharan Africa and other regions. But although debt ratios are lower than in the mid-1990s, debt has been creeping up for the past decade and the changing composition of creditors will make restructurings more complex.

Improvements to the Group of Twenty Common Framework for Debt Treatments—from which the 73 countries that were eligible for the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) in 2020-21 can now benefit—could clear a path through this increasing creditor complexity.

So far only a handful of countries have requested to use the common framework, which was launched in November 2020, underscoring the need for change to build confidence and encourage participation at a pivotal moment for heavily indebted low-income countries.

Rising risks of debt distress

Spurred by low interest rates, high investment needs, limited progress raising additional domestic revenue and stretched systems for managing public finances, the debt ratios of DSSI countries have increased, partly reversing a decline seen in the early 2000s.

Now, the economic shocks from COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine are adding to the debt challenges faced by low-income countries, even as central banks start to raise interest rates.

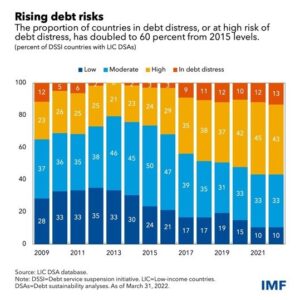

About 60 percent of DSSI countries are at high risk of debt distress or already in debt distress—when a country has started, or is about to start, a debt restructuring, or when a country is accumulating arrears.

Among the 41 DSSI countries at high risk of or in debt distress, Chad, Ethiopia, Somalia (under the HIPC framework) and Zambia have already requested a debt treatment. Around 20 others exhibit significant breaches of applicable high-risk thresholds, half of which also have low reserves, rising gross financing needs, or a combination of the two in 2022.

On the domestic side, difficult trade-offs will exist between the need to restructure sovereign debt owed to domestic banks, in some cases, and the impact of such restructurings on financial sector stability and the capacity of domestic banks to finance growth.

Local currency debt for the median DSSI country doubled from 7 percent of gross domestic product in 2010 to 15 percent in 2021. For those DSSI countries with market access, the share more than tripled from 8 percent to 28 percent in 2021.

Many of these DSSI countries have also experienced a tightening of sovereign-bank links, with larger holdings of domestic sovereign debt at domestic banks.

Coordination challenge

On the external side, increased diversity of creditors raises important coordination challenges.

In past decades, DSSI countries borrowed mainly from Paris Club official creditor nations and private banks, alongside multilateral institutions. Today, China and private bondholders play a much larger lending role.

The share of DSSI countries’ external debt owed to Paris Club creditors fell from 28 percent in 2006 to 11 percent in 2020. Over the same period, the share owed to China rose from 2 percent to 18 percent and the share of Eurobonds sold to private creditors increased from 3 percent to 11 percent.

The situation differs significantly across countries, however. Averages conceal a diversity of debt composition, from the shares of bilateral, multilateral and private creditors, to the composition of official bilateral creditors themselves.

China is now the largest official bilateral creditor in more than half of DSSI countries, including when counting all 22 Paris Club creditors as a single pool. China would therefore play a key role in most DSSI countries’ debt restructurings that would involve official bilateral creditors.

While the diversity of creditor compositions calls for greater attention to country specificities, appropriate coordination mechanisms will be key in all cases.

Common framework

Putting in place mechanisms that ensure coordination and confidence among creditors and debtors has become urgent. Improvements to the G20 Common Framework could play an important role by ensuring broad participation of creditors with fairer burden-sharing.

Experience so far shows that greater clarity on restructuring steps, earlier engagement of official creditors with the debtor and with private creditors, a standstill in debt service payments during negotiations, and specifying the mechanics of comparability of treatment is still needed.

Strengthening debt management and debt transparency should also be priorities. This would help countries manage debt risks, reduce the need for debt restructurings, and facilitate more efficient and durable resolution if debt becomes unsustainable.

It is in the interest of debtor countries as well as their creditors that debt restructurings, where necessary, are accomplished speedily, smoothly, and efficiently. This would support global stability and prosperity, too