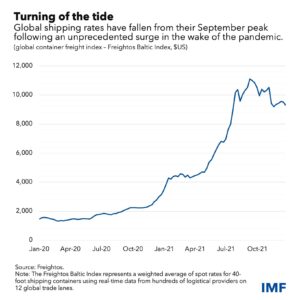

Shipping costs soared over the past year as consumers unleashed pent-up savings to buy new merchandise while the pandemic continued to snarl the world’s supply chains. Container rates have more than quadrupled since the start of the pandemic, with some of the biggest gains concentrated in the first three quarters of last year.

Lockdowns, labor shortages, and strains on logistics networks led to shipping-cost increases and significantly lengthened delivery times, though those pressures are easing. Our Chart of the Week shows how global container rates began to pull back from their record in September and have since declined by 16 percent, mostly due to falling rates for trans-Pacific eastbound routes, the main sea link from China to the United States.

The drop indicates that strong goods demand is diminishing after the traditional peak shipping season, which is typically from August to October. In addition, the US recently ordered some ports to expand operating hours and boost efficiency to reduce congestion and ease supply bottlenecks.

Although rates have subsided, they may remain elevated through the end of the year. Some underlying supply constraints do not have immediate fixes: backlogs and port delays, labor shortages in related occupations, supply chain disruptions moving inland, and shipping industry challenges such as the slow capacity growth and consolidation that concentrated the market power of a few carriers. On the other side, if the pandemic is controlled in the future, the demand for tradable goods might gradually decline as some service-providing sectors, such as travel and hospitality, recover.

Higher shipping costs and goods shortages are expected to boost merchandise prices. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) projects that if freight rates remain elevated through 2023, global import price levels and consumer price levels could rise by 10.6% and 1.5%, respectively. This impact would be disproportionately larger for small, developing islands which heavily rely on imports that arrive by sea.

Higher freight rates will also result in larger increases in the final price of low-value-added products. Smaller developing economies that export many of these goods could become less competitive and face difficulties with their economic recoveries. Moreover, the final prices of products that are highly integrated into global value chains such as electronics and computers will also be more affected by higher freight rates.

Returning to pre-pandemic shipping rates will require greater investment in infrastructure, digitalization in the freight industry, and implementation of trade facilitation measures