During early 2000, we all remember the famous quote by President Kuffour: “The golden age of business, where the private sector will be the engine of growth”. No wonder he launched the Public Private Partnership programme in 2004.

Currently, Ghana’s PPP Act passed by Parliament in 2020 seeks “to provide for the development, implementation and regulation of public private partnership arrangements between contracting authorities and private parties for the provision of infrastructure and services, to establish institutional arrangements for the regulation of public private partnerships, and to provide for related matters”.

Ghana, in the last two decades, has applied PPP concepts in various sectors which include transport (railways, roads, ports), sports infrastructure, IT infrastructure, hospital, office buildings, social infrastructure for the education sector, and other social infrastructure including markets.

After two decades of practice, it is opportune to assess the effectiveness of PPP policy in helping to finance government projects. At the aggregate level, PPPs were propelled to encourage private investors in government projects to surreptitiously propel the elimination of noticeable public financial debt. Hence, this article seeks to explore the PPP model and how if expanded it could help reduce Ghana’s huge public financial debt. It is critical for policymakers to explore the PPP model in various sectors to address the huge debts portfolio.

Overview of Public Private Partnership Model

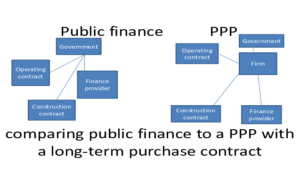

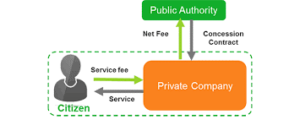

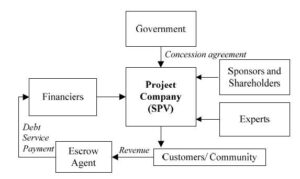

Public Private Partnerships simply involves a relationship between the public and private sectors. These relations are recognized by an enterprise agreement which empowers a distinct legal object in the practice of a ‘special purpose vehicle’ (SPV) formed under private proprietorship to finance, build and operate a government project for an agreed period. The SPV is also the legal owner of the project-related assets during the concession term.

One of the definite virtues of the PPP package is that there is a modicum boundary between government agencies and other parties, including users of the PPP service in the relationship cobweb. Once the project stretches to financial closure, most aspects of the contract’s execution and management are facilitated directly by the SPV.

The furthermost general options of PPP being adopted in Ghana is the Design, Build, Finance and Operate (DBFO) where the SPV is contracted to supply a bundling product. This product comprises two provisions: the provision of assets, such as buildings, roads and equipment; and the provision of services, such as asset maintenance, and cleaning and catering. Now, the question that needs to be addressed by policymakers is: why are we in a hurry to go and borrow to increase our debt, when we can opt for PPP finance model to address our challenges?

Public-Private Partnership and Debt Management in Ghana

The concept of PPP financing in government projects was to bridge the gap in financing and reduce government financial debts in Ghana. A typical government policy like ‘1 district-1 factory’ (1D1F) which is propelled by the private sector is a good example on how the private sector can support government in achieving its mandates.

However, the private investor’s involvement in Ghana has predominantly been the management of public service in the waste, energy, telecommunication and sanitation sectors. Significantly, with reference to core physical public infrastructures such as roads, railways, harbors and ports, airports, bridges and public hospitals, private investors’ involvement has been comparatively low.

The GoG has been the singular contributor for these physical public projects, using the national budget and international donor funds – which has rather resulted in an increment of our financial debt stocks. It has therefore become necessary in recent times for government to re-evaluate its policy and engage the private sector to assist in the delivery of more physical public infrastructures following the global financial crisis resulting from COVID-19, which has limited the flow of donor funds.

The low rate of PPP projects in Ghana could result from a plethora factors, even though PPP actually became a national policy in 2004 with the launch of a national policy guideline. A key factor in the lack of PPP implementation could be lack of understanding and skills of local practitioners.

In addition, not enough institutional structures are not in place to allow full-scale implementation of the policy, particularly for physical infrastructure projects. Thus, the PPP unit (i.e., Public Investment Division) established under the Ministry of Finance (MoF) should spearhead effective implementation of the policy so as to promote private investors and help reduce over-reliance on donors for funding.

As a matter of fact, the pace of PPP implementation in Ghana has been considerably slow, and more efforts from key stakeholders including government, private investors, civil society groups and academics are required in a national dialogue to see how adopting the PPP finance model can help reduce the country’s financial debt.

Conclusion

Within Ghana’s financial system, PPPs have been proven to be dominant financial schemes that address the financial gap of government in providing services and infrastructure without lifting government’s fiscal gauge beyond the ‘prudent’ level.

A typical government policy like ‘1 district-1 factory’ (1D1F) which is propelled by the private sector is a good example on how the private sector can support government in achieving its mandates. It is time for policymakers to rethink how PPPs can help finance projects and reduce public debt.

One way to strengthen this position is to segregate the oversight function of the PPP directorate (a function that carries the power to approve projects or reject PPPs that are not designated as being in the public interest) from the Ministry of Finance – hence the need to create an Authority with the mandate of promoting PPP projects in Ghana.

>>>the writer is a Researcher and Public Policy Analyst with considerable knowledge and expertise in Public Private Partnership, Leadership inspiration and Public Policy formulation.

He is currently a Senior Management Consultant, Gimpa Consultancy and Innovation Directorate (GCID), the Consulting Division of the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration (GIMPA. Contact the Author on 0205012686 / [email protected]