Alternative means of childbearing, which include but are not limited to surrogacy, have become increasingly popular in recent time. According to the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, in 2011 alone, there were 1,593 babies born in the U.S. to gestational surrogates as reported by Reuters (2013). Gestational surrogacy has proven to be one of the most viable options for women in whom carrying a pregnancy to term is contraindicated.

In surrogacy, various methods are used to form a viable embryo for pregnancy.

- With a donor’s egg

- With donor’s sperm

- With donor embryo

These factors associated with these methods affect the cost of surrogacy in Ghana. The average surrogacy cost in Ghana is GH¢150,000. This amount includes all the expenses from the required tests of intended parents and surrogates to the birth mother’s fee. Surrogacyforall.com stipulates that singleton pregnancy costs between US$49,000 and US$105,000 in the USA, while twin pregnancy poses an additional cost of US$5,000.

One report by BBC, (2018) states that financially and socially vulnerable women can be targets for surrogacy recruitment, since they are attracted by the huge sums of money on offer. For instance, a surrogate in Ukraine can earn up to US$20,000 (£15,507); more than eight times the average yearly income.

Despite being a seemingly lucrative venture considering the money involved, there have been reports of poor treatment of surrogate mothers, with some agencies refusing to pay surrogates if they do not obey strict requirements or if they miscarry. Exploitation concerns have led to many countries shutting down their previously booming surrogacy industries. In 2018, a report by ohchr.org, stated that the UN warned that “commercial surrogacy….amounts to the sale of children”.

What is surrogacy?

According to Dr. Owusu-Ansah, Surrogacy is when someone carries a child for a woman, who due to complications, is unable to do so naturally. The child is carried till delivery. Wikipedia, (2021) has also defined Surrogacy as “an arrangement, often supported by a legal agreement, whereby a woman (the surrogate mother) agrees to bear a child for another person or persons, who will become the child’s parent(s) after birth.”

Types of surrogacy

The term “surrogacy” is generally used to describe a couple of different scenarios.

- A gestational carrier carries a pregnancy for an individual or couple using an egg that is not the carrier’s. The egg may come from either the intended mother or a donor. Likewise, sperm may come from the intended father or a donor. Pregnancy is achieved through in vitro fertilization (IVF).

- A traditional surrogate both donates her own egg and carries a pregnancy for an individual or couple. The pregnancy is usually achieved through intrauterine insemination (IUI) with sperm from the intended father. Donor sperm may also be used.

According to the Southern Surrogacy agency, gestational carriers are now more common than traditional surrogates. This is due to the fact that once a traditional surrogate donates her own egg, she is technically also the biological mother of the child, and has genetic ties to the said child.

How does surrogacy work?

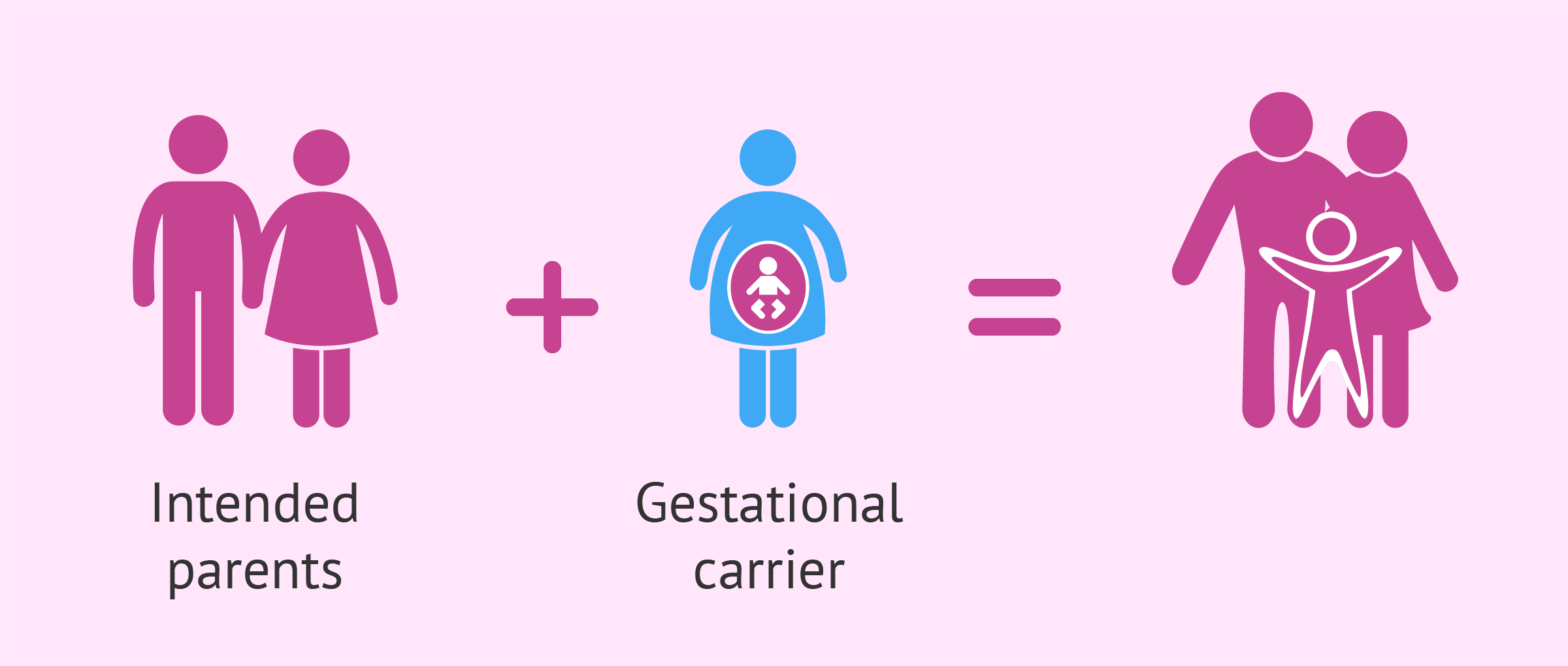

Gestational surrogacy helps those who are unable to have children become parents. It’s a process that requires medical and legal expertise, as well as a strong support process throughout the journey.

Through IVF, embryos are created in a lab at a fertility clinic. Sometimes the intended parents use their own genetic material. Sometimes, an egg donor is required. At the fertility clinic, 1-2 embryos are implanted into a gestational carrier, who carries the baby(ies) to term. Gestational carriers have no genetic relationship to the children they deliver.

Surrogacy and the law

Many countries do not have legislations on Surrogacy and this presents with many challenges. For instance, the case of baby Gammy as reported by the BBC (2016) shocked the world, when it was alleged the commissioning parents had intentionally left Gammy, who had Down’s syndrome, in Thailand, while taking his non-disabled twin sister Pipah home to Australia. A court later ruled, according to Telegraph, (2016), that he had not been abandoned, although it emerged the commissioning father had previous convictions for child sex offences, playing into wider concerns regarding the welfare of surrogate children.

In Ghana, there is currently no law regulating the practice of surrogacy. According to the SurrogacyLawyers.com, “Regardless of the law in Ghana or any other destination, the surrogate is always the legal mother. Whether or not one of you is the legal parent will depend on the circumstances surrounding the insemination or embryo transfer, and whether the surrogate is married or in a civil partnership. Thus, it is essential that you get advice before you start the process and preferably, before you select the surrogate. A Parental Order extinguishes any legal rights that the surrogate and her husband have for the child and makes you the legal parents. If you do not apply for a Parental Order by the time the child is 6 months old, you may need to consider alternatives such as adoption. This deadline has been extended in some cases.”.

According to Dr. Owusu-Ansah in an interview with naaoyooquartey.com, “all proceedings are covered by a written agreement between all parties involved including medical staff, surrogate, commissioning parents etc”.

He further emphasized that some surrogates become a bit resistant after delivery because they feel they haven’t been adequately compensated or well treated during the 9-month period, whilst others feel an emotional bond to the child after delivery. “That’s why consent forms are signed before the process begins to prevent conflicts. If there’s any issue, discussions can be held to resolve any contentions”.

The challenge here is that legislation concerning surrogacy varies hugely from country to country and is shaped by history, culture and social values. For instance, in Germany and France, surrogacy is seen as violating the dignity of women, using them as the means to someone else’s end.

Therefore, the practice is completely forbidden. Other jurisdictions like the UK view surrogacy as a gift from one woman to another, and allow it on an “altruistic”, expenses-only basis. Others still, such as California, Russia and Ukraine, permit commercial surrogacy, viewing it as an expression of a woman’s autonomy to engage in surrogacy of her own free will.

Ukraine is one of the few countries in the world where the law approves and duly regulates the usage of Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) services; surrogacy and egg donation in particular. Article 123 of the Family code of Ukraine confirms the child born from surrogate mother as a result of usage of assisted reproductive technologies belongs to the Intended Parents and their names come in baby’s birth certificate. The total cost of a surrogacy program with Self Eggs starts from €40,000 “Success Package” with up to four Embryo Transfer Attempts, while “Guaranteed Surrogacy” Packages are also available at affordable costs (tentative US$50,000- US$56,000).

Georgia is another trending destination for Surrogacy, here a heterosexual couple is qualified to get the surrogacy. They do not prohibit any couple for having surrogacy, but it is the duty of the clients to verify from their home country as the baby is their property. The cost for surrogacy is between US$38,000- US$40,000 for self-eggs and donor’s eggs respectively.

In India, Surrogacy exists for only Indian citizens. The cost of surrogacy in India is INR13,00,000 to INR 15,00,000 [US$20,000 – US$23,000] with own eggs or donor eggs.

Some international surrogacy destinations, such as Kenya and Nigeria, remain unregulated. Kenya, currently has a bill on surrogacy which is yet to be passed. The current surrogacy legislation in Kenya makes it an attractive destination for “reproductive tourists and especially Egg Donation and Surrogacy Programs”. The total cost for self-eggs or Caucasian / African Donor Surrogacy program is US$45,000 approximately.

Discrimination when sperm donor is used

This has been evident in the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights, where recent cases have focused on the need for legal recognition of biological ties. In Mennesson and Labasee v France (Appl. Nos. 65192/11 and 65941/11) Judgment of 26 June 2014; the applicants were two French couples, and their children born in the USA as a result of surrogacy arrangements.

When they returned to France, the French authorities refused to register the children’s birth certificate on the French Register of Births, on the grounds that recording such entries would give effect to a surrogacy agreement that was null and void under French law and recognize a practice that the legislature had expressly forbidden.

The Court took a very insensitive approach to the claims of the parents, finding that the difficulties they faced in having to produce a foreign birth certificate were not insurmountable, and that they had failed to demonstrate that the failure to obtain recognition of their parentage had hampered the enjoyment of their right to respect for family life.

However, the Court found that the children’s rights had been violated. The Court focused on the right to respect for private life on the part of the child, emphasizing that this encompasses the right to establish details of one’s identity, as well as the recognition of the legal parent-child relationship.

Noting the lack of clarity regarding the children’s legal status, the Court observed that they faced uncertainty concerning the possibility of obtaining French nationality, which undermined their identity within French society. It noted that nationality and a right to inheritance were also important elements of a child’s identity, and these had been compromised by the refusal to recognize parenthood.

Although the children’s genetic fathers were French, they were unable to obtain French nationality, and they were only able to inherit from the commissioning parents as legatees, rather than as descendants.

As such, the Court considered that their situation was liable to have negative repercussions on the definition of their identity. It found that “given the importance of biological parentage as part of one’s identity, one cannot claim that it is in the interests of a child to deprive him of a legal relationship of this nature while the biological reality of this link is established, and the child and parent concerned demand full recognition”. Thus, the biological link with the father was framed as the crucial component in the creation of an interest in private life for the child.

In the US, the watershed Baby M case, which happened in 1987 in New Jersey, was the first locus classicus involving surrogate parent arrangements. The case stipulated that Mary Beth Whitehead had contracted with William and Elizabeth Stern, to act as a surrogate mother for them. She was impregnated with an embryo (made by her egg was fertilized with Stern’s sperm), and after carrying the child to term, had a change of heart about handing the baby over to the couple. Whitehead sued for custody of the child. Finally, the New Jersey Supreme Court declared that blood was thicker than paper. The Court held: “contract with the intended parents invalid”. The court stated that the government could not enforce a contact that orders a fit and loving mother to give away her child. Whitehead was denied custody, but granted visitation rights.

Another case heard by a state Supreme Court took place in California in 1993. Johnson v. Calvert, 1993, resulted in a contrasting ruling to the Baby M case. Mark and Crispina Calvert hired Anna Johnson to carry to term their genetic child. Johnson ultimately sued for custody of the child. In a 6-1 decision, the California Supreme Court ruled that Johnson had no parental rights to the child.

This was the first time a state high court enforced a surrogacy contract. “It is not the role of the judiciary to inhibit the use of reproductive technology when the legislature has not seen fit to do so,” wrote Justice Edward Panelli for the majority. The court’s only woman, Justice Joyce Kennard, wrote in a sharply worded dissent: “A pregnant woman is more than a mere container or breeding animal; she is the conscious agent of creation no less than the genetic mother, and her humanity implicated on a deep level. Her role should not be devalued.” The court has reaffirmed this finding several times since 1993.

Further is the Beasley case (2001), where a 26-year-old British woman was hired to carry to term a child intended for a California couple for nearly US$20,000. Beasley realized 8 weeks into her pregnancy that she was carrying twins. Her contract with the couple stipulated that she would undergo a “selective reduction” if she became pregnant with more than one fetus. Realizing that about the twins, the couple arranged for Beasley to “reduce” the number of fetuses by one.

Beasely refused on the grounds that she was too far into the pregnancy to undergo the procedure. Effectively, these actions could have amounted to the couple requiring an abortion of an unwilling mother. Beasley acknowledged that she has no legal rights to the children, but now did not want the intended couple to have them. “I believe these parents have made it expressly clear that they have not wanted these children.” Another couple took over the surrogacy contract.

The Buzzanca case (1998)

In this California case, a complicated intersection of surrogacy contracts and artificial inseminations left an unborn child legally parentless. Providing an account of the case, Blum, (2006) states that the couple accepted to have an embryo genetically unrelated to them implanted in a surrogate mother who would carry the child to term for them. Just before the baby was born, Mr. Buzzanca filed for divorce. He claimed that there were no children born to the marriage and that he was not responsible for the child born to the surrogate, financially or otherwise.

The case was brought to trial in a California lower court, which was responsible for determining who the lawful parents of the child were. The court at first concluded that the child had no lawful parents because the intended couple had no biological relationship to the child. An appellate court eventually overturned this decision, finding the Buzzancas the legal parents, stating that a genetic tie is not determinative and that rather, the intention of the parties was controlling. Luanne Buzzanca now has custody of the child, and her ex-husband is paying child support.

The Fasano case (1999)

In this New York case, Donna and Richard Fasano contracted with a fertility clinic to implant two of their fertilized eggs into her uterus. Nine months later, she had twins. One was white and the other black. The clinic had mixed up its fertilized eggs, implanting one of theirs and one belonging to a black couple. The Fasanos eventually had to turn over the baby to its biological parents but sued for visitation rights. The court decided that Donna’s motherhood was only “nominal” and denied the Fasanos visitation. Now the biological parents are suing the fertility clinic for negligence.

Blum, (2006) emphasized that this case centered on property rights, bringing the following question to the fore: Are frozen embryos in a lab’s test tube “people” or are they “property?” If embryos are property, they can be awarded to either person in a divorce, like any asset; if they are people, then custody laws become relevant, and an important factor is who the better parent will be.

The Turczyn case (1997-8).

On this account, Blum, (2006) stipulates that Debbie and Michael Turczyn were separated in 1996 when she decided to become artificially inseminated by an anonymous sperm donor. The couple reconciled, and with Michael’s support, Debbie gave birth to quadruplets. Nine months later, Michael moved out again and Debbie filed for divorce. She sued him for child support. A lower court and the Pennsylvania Superior court ordered that Michael had held the children to be his own throughout the pregnancy, and that in this case, conduct trumped biology.

Michael and his lawyer appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, who refused to hear the case again. The court held that the lower courts were right in finding that Michael was the legal father by reasons of estoppel. There were no legal guidelines in terms of how long a person has assumed a parental role before being considered a legal parent. As Michael’s lawyer said, “It’s a case by case basis, which leaves plenty of room for a judge’s discretion. One judge might say four months is absolutely too short a time, another judge may say five years is too short a time.”

In another case in South Africa, surrogacy was legally recognized and regulated by Chapter 19 of the Children ‘s Act, 2005, Act 38. The Children’s Act takes cognizance of in vitro fertilization, and section 1 of the Act defines a surrogate agreement as “an agreement between a surrogate mother and a commissioning parent in which it is agreed that the surrogate mother will be artificially fertilized for the purpose of bearing a child for the commissioning parent and in which the surrogate mother undertakes to hand over such a child to the commissioning parent upon its birth, or within a reasonable time thereafter, with the intention that the child concerned becomes the legitimate child of the commissioning parent”

For a surrogate agreement to be valid in South Africa, such an agreement must be in writing and signed by the parties and the surrogate mother and at least one of the commissioning parents must be domiciled in South Africa at the time of entering into the agreement. Such agreement must be confirmed by the High Court.

Only gestational surrogacy is permitted in South Africa. Furthermore, commercial surrogacy is expressly prohibited by section 301 of the Children’s Act, and the only compensation that a surrogate mother may claim is limited to the direct expenses of artificial insemination; pregnancy; the birth of the child; loss of earnings suffered by the surrogate mother as a result of surrogacy; and insurance associated with the pregnancy.

The permissible payments in respect of a surrogate agreement was confirmed in Ex Parte HP & Others 2017 (4) SA 528 (GP). A violation of this requirement attracts a fine or imprisonment of a maximum of 10 years or both fine and imprisonment Per Sec 305(6) Children’s Act.

The rights of a surrogate mother in South Africa are protected, to the extent that a surrogate mother has the right to terminate the surrogate motherhood agreement within six months of giving birth to the child by filing for a notice in court

Conclusion

As Health Care Policy Researchers, we are concerned with the rise of surrogacy arrangements in Ghana without protection for the Surrogate mothers. We believe their rights need to be protected by law and therefore we believe that, Ghana needs an urgent legislation on Surrogacy.

Prof. Raphael Nyarkotey Obu is the president of Nyarkotey college of Holistic Medicine and final year LLB Law student. Lawrencia Aggrey-Bluwey is an Assistant Lecturer with theDepartment of Health Administration and Education, University of Education, Winneba, and is currently a PhD student in Health Policy and Management at the University of Ghana Business School.