Reviewed by: Rev. Dr. Christian Tsekpoe, Head of Mission Department, Pentecost University.

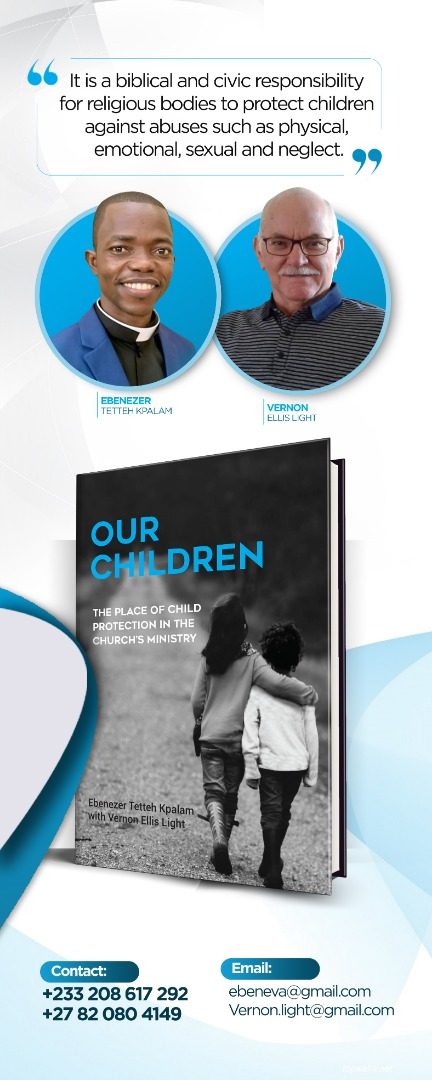

Book Title: Our Children: The Place of Child Protection in the Church’s Ministry

Authors: Ebenezer Tetteh Kpalam with Venon Ellis Light

Publishers: Kinder Foundation, Accra (2020).

ISBN: 979-8599-2-3187-5

Pages: 122

In this book, Our Children: The Place of Child Protection in the Church’s Ministry Ebenezer Tetteh Kpalam and Venon Ellis Light have taken a bold step by providing what I consider a manual for unlocking this paradox, and responding to the plight of our children. This short book amazingly places an impressive resource material for child protection at the reach of all. It is not a book for only Children’s Ministry workers; it is a book for all parents, church leaders, teachers and children themselves. The book identifies that “The true extent of violence against children is impossible to measure. This is because much of it occurs in the secret and not reported” (p. 3).

This research on child protection in Sub-Saharan Africa and from a Pentecostal setting is timely. In Africa, childbirth is seen as prestigious, esteemed and significant. It is celebrated to the extent that childless couples suffer a kind of family pressure to give birth and sometimes stigmatisation from a whole society. This attitude, though not acceptable seems to suggest that children are considered very important and childlessness approached with disdain in some African certain. In a regrettable paradox, however, children in Africa, as observed elsewhere around the globe, suffer abuse, oppression, subjugation, manipulation and violence in many ways unimaginable.

Revealing some staggering statistics on child abuse, the authors indicate that child abuse can take the form emotional abuse such as neglect, terrorising, humiliating, defaming, ostracising and blackmailing. It can also be physical abuse such as poking, punching, shoving, hair-pulling, biting, beating, stabbing, burning, strangling, suffocating and poisoning. Other forms of abuse include verbal abuse, relational abuse or child abandonment (pp. 4-5). I hear the authors saying silently in each lines of the book, “This abuse must stop!”

The book can be generally divided into two sections. Section one comprises of Chapters One to Four. This section analyses historical and theological perspectives of child protection. In Chapter One, for example, the authors give the general introduction to the book, indicating the motivation for writing a book on child protection and highlighting the problem of child abuse. Chapter Two discusses a biblical theology of child protection. Beginning from the Gospels, the authors used Jesus’ metaphor of the good shepherd who protects his flock (God’s people, including children) and encourages the church to imitate Jesus in protecting the vulnerable and oppressed, especially children in society. The authors further analyse both Old and New Testament teachings in this chapter as a guide for child protection (Pp. 13-28).

Chapter Three brings out a historical theology of child protection. The chapter discusses how Apostolic Fathers such as Ignatius, Justin Martyr, Aristides and Polycarp interpreted the Bible and responded to child abuse by promoting adoption and orphan care within the late first century (pp. 30-34). The authors brought light on child protection during the Middle Ages, the Reformation as well as the Eighteenth Century and beyond, and concluded that “The vulnerability of children in society has never been uncommon. Right from the era of post-apostolic Church to date, huge numbers of children have been neglected, rendered homeless and often abused. As a result, Christians have made conscious efforts to respond to the plight of vulnerable children, and also ensured that children grow to become mature and fulfilled Christian adults” (p. 38). Chapter Four, discusses the subject from the perspective of systematic theology. The chapter engenders the relationship between systematic theology and biblical theology, historical theology as well as social and medical sciences. It finally suggests a theological model of child protection for the contemporary church.

Section Two of the book comprises of Chapters Five to Seven. This section discusses the concept of child protection in the Church of Pentecost, using the Winneba Area as a case study. In Chapter Four, the authors qualitatively analyse the understanding of child protection among the leaders of some specific district in the CoP Winneba Area, identifying and analysing the weaknesses and challenges of the practice of child protection in the church. Chapters Six and Seven propose a step-by-step strategy for achieving effective child protection and nurturing in the contemporary Church. The recommendations of the book and the appendixes are equally vital as the analysis by providing the Church with tools for protecting our children.

The authors succinctly conclude by agreeing with Van Rensburg that “There is no unreached children or youth. If the Church doesn’t reach them, someone will – other faiths, political ideologies, secularism, corporate marketing, people traffickers, or a myriad of other frightening and unwholesome possibilities” (Pp. 82-83). Although the sample size for the study was limited to a small-scale qualitative study, the discussions in this book is timely and colossal. As a missiologist, I see this book as mission to the next generation and I recommend it for all – parents, teachers, church leaders and children workers.