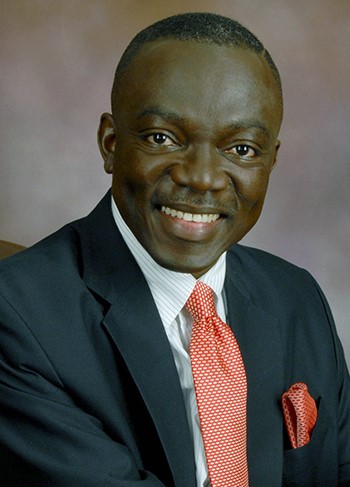

Strategic Sourcing and Industrialisation insights with Prof Douglas Boateng

Contrary to popular belief, there is a supply chain associated with every tangible or intangible product emanating from among others.

Public sector agencies and institutions (e.g. services from the Judiciary, Police, Correctional services, National Identification Authority, the Electoral, Public and Civil service Commissions etc ); ministries (eg Water and Sanitation Defense, Trade and industry, Women and Children Affairs, Finance and Economic Planning, Agriculture, Tourism, Health, Transport, Railways, Justice and Attorney General, Works and Housing, Roads, Information, Foreign Affairs, Youth and Sports, Energy, Communications, Local and rural government etc) and sectors (eg chemicals and oil, agro-processing, retail, forestry, consulting, telecommunications, education, pharmaceuticals, logistics and distribution, media, construction, textiles, fishing, military, printing, ICT, publishing, automotive, electronics, aviation, maritime, mining, exploration, waste collection, financial services, hospitality, entertainment, manufacturing, electricity, power generation, etc.

In the past nine months, these supply chains have all witnessed interruptions never before experienced in the post-modern era. The need to adjust to the unprecedented global disruptions caused by COVID-19 has compelled entities within these channels to seek innovative ways to reconfigure themselves, resulting in new challenges and opportunities.

To resolve some of these complications, some c-suite executives, national leaders and policy makers are increasingly looking to adapt various aspects of supply chain management (SCM) to help further advance long-term industrialisation and selected socio-economic developmental objectives.

So, what is supply chain management (SCM)? Put simply, it is the conscious effort to manage all the interlinked value-adding activities that goods and services encounter as they move through a value-chain en route to the ultimate user.

In Africa and the emerging world, many practitioners still consider supply chain management and procurement to be the same. However, over the last twenty years, various academics and seasoned industry professionals including Lambert D and Lee H, have successfully managed to distinguish between the two.

Today, SCM is one of the core functions within organisations and government which is recognised as being on par with business functions such as finance, legal, marketing and information technology. At the core of supply chain management is the need for collaboration for long-term mutual benefit. By its nature, SCM helps to break down silos and self-centred thinking within a value chain, thus ensuring the creation of a shared vision for sustainable long-term, ‘win-win’ outcomes. Other elements of supply chain management include logistics and procurement

Procurement primarily focuses on the acquisitive process within supply chain management. A rapidly emerging key aspect of procurement is strategic sourcing (SS).

The US General Services and Administration describes strategic sourcing as a structured and collaborative process of critically analysing an organisation’s spending patterns to better leverage its purchasing power, reduce costs, and improve overall performance.

Purchasing Insights sees strategic sourcing as an approach to procurement whereby the business needs of the organisation are matched with the supplier market. Today, strategic sourcing is increasingly being applied by c-suite executives to help maximise every cent spent on sourcing products for the benefit of their organisations, industry and society as whole.

The Chartered institute of Procurement and Supply (CIPS) describes strategic sourcing as a core activity in procurement and supply aimed at “satisfying business needs from markets via the proactive and planned analysis of supply”. One of the basic tenets of SS, according to CIPS, is spend visibility – the detailed and reliable view of what an organisation, be it public or private, uses to acquire goods and services.

Strategic sourcing requires extensive knowledge and competence. Its goal is to satisfy organisational needs via the proactive and planned analysis of demand and linking it to related suppliers. The objective is to deliver solutions to meet pre-determined and agreed upon organisational needs and increasingly industrial and society goals.

Gartner summarily describes SS as a “standardised and systematic approach to supply chain management that formalises the way that information is gathered and used thus enabling organisations to leverage their consolidated purchasing power to find the best possible value in the marketplace”.

Accenture views strategic sourcing as a means to “wring waste out of acquisitions…which could generate immediate savings of up 15% of total addressable spend.” It is geared towards ensuring that resources are utilised optimally to benefit the entire value chain. It does not merely concentrate on what an organisation is buying, but rather prompts the process custodian to continuously appraise a sourced-in product according to world class benchmarks.

To others, including Lambert D, Lee H, Christopher M, Boateng D, Rogers S, et al, strategic sourcing is not just about acquiring to meet organisational needs but also to satisfy other industrial and societal developmental needs.

It is coined as ‘strategic’ primarily because it focuses on medium-long term objectives and assists in the leveraging of public and private sector organisational spend. It is not about price chiseling but rather a means to add real value to business, industry and society.

Evidence from among others China, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, Mexico, Germany, Singapore and Malaysia show that SS can be a catalyst for the development of marginalised regions, industries and small-to-medium sized businesses. When properly adapted, it has resulted in: growth in the local economy, the creation of jobs, local value addition, improvement in service delivery quality, sectorial industrialisation, empowerment of women, the youth, enterprise development and value for money.

With significant value chain improvements, savings and wider societal and developmental gains can be achieved if public and private sector organisations/institutions strategically source and manage their tangible and intangible requirements.

Some recent research into strategic sourcing in Africa revealed that in the private sector, strategic sourcing is assisting organisations to achieve quantifiable savings; often between 8% and 30% on procurement expenditure.

As a proven catalyst for industrialisation, a number of countries including Rwanda, South Africa, Mauritius, Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria are looking to adapt SS for public sector acquisition to help boost selected sectors.

Some of the key aspects of strategic sourcing include:

- understanding, predicting and even driving market forces impacting on a supply chain;

- developing and executing sourcing strategies is linked to overall business strategy and sectorial and society development;

- proactively managing supplier relationships to deliver optimal value; and

- creating a total organisational culture and process to best incorporate value from suppliers.

Private and public sector organisations planning to use the power of strategic sourcing to facilitate long-term socio-economic development, industrialisation and poverty reduction should: (a) look to include SS modus operandi as an integral part of enterprise-wide business strategy that is beneficial to all those involved; (b) identify the changes necessary to move towards a strategic sourcing approach; and (c) ensure that this new approach and its benefits for the organisation and society at large is communicated.

In Africa, a general focus on price continues to hamper opportunities for strategic sourcing. It is now an accepted fact in emerging economies that ‘price’ weighting can be a hinderance to job creation and localisation strategies as it generally favours multinationals and big organisations at the expense of small and medium-sized corporations. South Africa and Ghana are case examples whereby despite enacted policies such as the Preferential Procurement Policy Act and “minuscule sections” of the Act 663 respectively which are intended to favour emerging local suppliers, women and the youth, a continued emphasis on price, remains an obstacle for industrialisation, local supplier and enterprise development.

The centrality of strategic sourcing to long-term economic development is without question and now generally accepted by many African governments and administrations. However, its medium-to-long term benefits are sometimes difficult to comprehend as the gains normally materialise over a three-to ten-year time frame.

In line with the Africa Beyond Aid Agenda (ABA), the UN Sustainable Development Goal (UNSDGS) and the Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) South Africa, Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda, Nigeria, Morocco and Ethiopia among others are through strategic sourcing, already gradually advancing their respective agendas to empower women and the youth.

This has involved the aggressive industrialization of selected sub-sectors in food and beverage processing, chemicals, maritime, aviation, logistics and distribution, fishing, textiles, construction, agriculture, manufacturing, oil, healthcare, education, waste and water services, financial services, minerals and metals, hospitality, entertainment, telecommunication and ICT.

In summary, supply chain dynamics are going through unprecedented changes. Hitherto, the role of an entity in the value creating channel was seen as discrete and self-contained. This is not the case anymore. The new and post COVID-19 landscape requires that an organisation be it public or private collaborates plus manages amongst others, multiple technologies, suppliers, regulations, customers, governments, communities and cultures.

To conclude, the scope and long-term societal impact of strategic sourcing in developing and managing emerging world supply chains is undeniably significant. However, it takes time for the quantifiable benefits to become apparent. It is therefore critically important that each African country devises a strategic sourcing agenda appropriate for its long-term sectorial industrialisation and socio-developmental goals.

Douglas Boateng, Africa’s first ever appointed Professor Extraordinaire for supply and value chain management (SBL UNISA), is an International Professional certified Chartered Director and an adjunct academic. Independently recognised as one of the vertical specific global strategic thinkers on industrialization, supply and value chain governance and development, he continues to play leading academic and industrial roles in sectorial reforms both in Africa, and around the world.

He has received independent recognitions and numerous lifetime achievement awards for his extraordinary contribution to the academic and industrial advancement of supply chain management from various international organisations including the Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply, the Commonwealth Business Council and American multi-national Hewlett Packard (HP). For more information visit www.douglasboateng.com and www.panavest.com