COVID-19 is taking us all through a steep learning curve. It’s like one of those classes everyone swears might be useful in the future, but you are certain you can do without. And to survive, we have had to make major sacrifices, hoping to come out with our report cards not completely destroyed.

Ghana, West Africa’s second-largest economy by population and economic output, faces the triple whammy of a health crisis, global economic downturn, and a commodity shock. The sad part? As the pandemic prods and tugs at the stability of the economy, it is doing even worse damage by inflicting a human toll on the population, claiming some 66 lives too many, in some distorted wicked dance.

The world doesn’t quite have answers to a lot of the tough questions this pandemic stares us down with each day. What we do know is that the current global pandemic requires us to be willing to think more creatively about our responses, as well as to take an all-hands on deck approach. We need all the resources we can get. One such resource is the diaspora, the estimated 4 million (conservative figure) global citizens, who maintain a feeling of transnational community with the nation.

Diaspora communities are important. For the longest time, they have contributed to economic development in Africa through welfare transfers in the form of remittances. At the household level, remittances have helped smooth consumption expenditure and increased household spending on health, education and small business, and also reduced poverty.

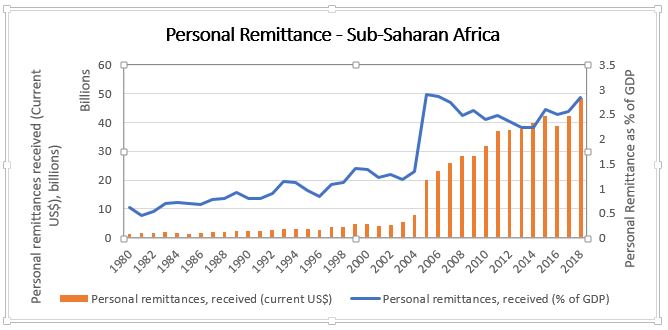

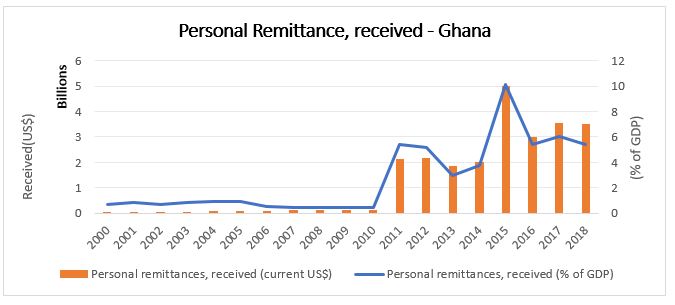

According to the World Bank, remittance flows to low- and middle-income countries alone was more than three times that of official development assistance, before the crisis. As the more stable source of external capital flows, more than private investment or development aid, remittance contributes to the economic wellbeing of numerous countries. In sub-Saharan African and before COVID-19, officially recorded remittances amounted to a record $48 billion in 2019, $15 billion more than net FDI inflows in the same year. This does not include indirect sources such as monies sent with families, friends, acquaintances, and sometimes foes. Nigeria, for instance, in a paper by PwC was estimated to have received some $25 billion in remittances in 2018, representing 6% of GDP and translating into near 80% of the Federal government’s budget, ten times more than FDI flows, and up to seven times the value of net official development received in 2018 of $3.3billion.

As a result of the pandemic, remittances from diaspora communities are declining due to layoffs, delayed salary payments, and uncertainty around future incomes in Europe, the USA, and the Middle East where most of the diaspora communities live and work. Remittance flows to Sub-Saharan African are expected to see a 23% decline, albeit with modest recovery expected in 2021. This means reduced supplementary income for many individuals which has repercussions for spending on food, health, education, and general living. For many, this is another crisis altogether.

History teaches, especially from the examples of the East Asian countries of Japan, Vietnam, South Korea, that crises can bring opportunity if you are willing to take it. We have an odd, yet timely, opportunity to channel the emotional ties of the diaspora into more strategic and operational purposes in the homeland.

The knowledge, professional skills, time, and resources of Ghana’s diaspora need to be directed to strategic use – addressing Ghana’s biggest challenges. The investment of funds and talent need to be focused on areas such as education, whether it be building infrastructure, teaching support, or providing strategy to upgrade the curricula. If people from Logba can be guided by a proposal to build two additional schools and a well-resourced tech hub, will people not rally behind advancing their places of birth? The places where their cousins, aunties, and grandmother live? This may work better as opposed to a broader call for partnerships to build schools all over the country – an approach that may work but on a very limited scale as Ghana’s trajectory so far shows. The same can apply to infrastructure, healthcare, agribusiness, and others.

That is not to say that the diaspora is a silver bullet for all Ghana’s issues. The idea is simple but certainly not simplistic.

But it sure is one way to leverage the expertise and knowledge of more ‘developed’ countries. Professors in the diaspora can devote a portion of their time to lecture students back home through online portals, or during the summer where they can lead in-person sessions. Health care professionals can share the best practice and more cutting-edge knowledge they have amassed from Cuba to Switzerland. Tech brains flourishing in San Francisco, Dublin, New York, and London can lend their adeptness to solving some age-old challenges in agriculture, health, financial inclusiveness, you name it. The opportunities are endless.

What does this require?

First, Ghana needs to identify where its diaspora is; who they are; what they do; what they are willing to do; and how Ghana can help make it easier for them to engage. Ghana needs data – updated and relevant data. Such information would allow the tailoring of diaspora engagement to the different constituencies that exist beyond Ghana’s borders. Affluent diaspora members, for instance, can be tapped to help expand Ghana’s network and goals around foreign direct investment, making introductions where needed, providing insight and context where needed, and backing deals where needed.

Second, success will require a clear outline of those key sectors and areas where Ghana is short of skills and capacity, what exactly it needs in those areas, how much it needs, and when its diaspora is needed to fill those gaps.

Thirdly and more pragmatic, Ghana needs to explore and outline the feasibility of incentives for returning migrants who wish to set up businesses for instance. Ghana needs to consider ways to reduce the barriers to ‘return’, including visas and visas for spouses; reducing the costs of transferring money back to the motherland; developing relevant tourism products, etc. It needs a clear value proposition with all perks clearly established. After all, they may be long lost friends, family or warm contacts the nation is trying to engage but it is strictly business. And they needed to be treated as customers.

Lastly, Ghana needs to develop a policy environment that is appropriate, conducive, and stands to benefits all parties involved: the diaspora, the homeland, and the diaspora in their host lands. Success is crafting a strategy that leads to the reaping of the country’s “diaspora dividend.”

The point should not be to suck the diaspora dry but rather to acknowledge the inherent power in diaspora relations, and networks.

In the current global context, Ghana, like many other countries, will be left with a gaping hole in its pocket and in need of an ‘all minds’ approach to addressing its challenges. Everyone is looking for answers, and the competition for resources will be dire. What better way to get ahead than by leveraging the global minds, talents, connections, and resources of Ghana’s very own? Anecdotal evidence shows how everyone who has left the shores of Ghana has met someone who has a Ghanaian professor, fellow Ph.D. student, or manager they remember fondly. The reputation and accomplishments of Ghanaian professionals outside is one that must be tapped into to advance the domestic social, economic, environmental, and cultural spheres of Ghanaian life.

There will be challenges in building out diaspora relations.

Managing the tensions between domestic populations and those people who left (or escaped); managing the desire of the diaspora to impose ideas picked up elsewhere; managing the ill-feelings of diasporic communities such that they do not feel like money bags. There will be many. But these are not beyond resolve, if there is a thought-out plan. One that is based on the need to build mutually beneficial relationships.

Diaspora engagement has been key to recent successes in many states including Ireland, India, China, Kosovo, and Israel. Simply by connecting and engaging with their diaspora communities in the U.S.A, for instance. There is a lot to be garnered from the experiences of these countries and the beauty about it is that with diaspora engagement, Ghana doesn’t have to do something extraordinarily new. As diaspora exerts says, ‘there is no competition for your own people so replicate where you see fit’. The lesson? It’s about learning what others have done well and assessing whether such approaches could work as a successful prototype of engagement in Ghana, for instance, taking into consideration the nations unique strengths.

Unfortunately, no one can do this for Ghana. It must take the reins. While diaspora engagement is most successfully led by players outside of government, it needs help across board. What the government needs to do is to facilitate the process and enable diaspora participation and ownership. And for this, political will is necessary – the kind that backed the Year of Return initiative in 2019. All-hands on deck approach.

Ghana, and much of Africa, must act on its current realities. The odds are stacked against many countries, and the way out does not entirely appear clear yet. Those who succeed will be those willing to try new things, think differently than they have in the past, and be willing to act. Perhaps now is a chance for Ghana to do things differently with what it has always had.

The writer is a researcher at the Johannesburg-based think tank, the Brenthurst Foundation. She writes in her capacity as an inquiring Ghanaian. For more insights, see here.