In development lexicon peace, stability and economic growth have been described as mutually reinforcing and have the collective power to spur inclusive development. This is why Ghana’s institutions and those who manage them; as well as individuals and groups must always put the peace and stability of the country at the forefront of policy formulation and decision making.

For the second consecutive year Ghana has been ranked among the most peaceful countries in West Africa and third on the continent in the 2020 Global Peace Index report. In 2019, Ghana obtained the same position in the sub-region, but has improved one step further on the continent as it placed fourth last year.

Strangely, the release of the peace index always coincides with a national event that threatens peace and stability. In fact, the 2019 index came to me as a shock, viewed against the background of propaganda by some pressure and interest groups that Ghana was heading for a meltdown after Ayawaso West Wuogon bye-election. During and after the bye-election a well-orchestrated plan was unleashed to disrupt the bye-election, but the plan was met with an equally well-planned national security backlash.

War drums

Prior to the release of the current index, some interest groups were beating war drums about violence and insecurity if the Electoral Commission of Ghana (EC) goes ahead with the compilation of a new voter register. Like the 2019 Index which doused the flames of insecurity, the 2020 Index has reaffirmed our collective conviction that Ghana is a peaceful country, heading for the 2020 general elections.

The Global Peace Index (GPI) is compiled by the Institute for Economics & Peace (IPE) based in Sydney, Australia. The rankings are determined based on how a country fares in three categories: societal safety and security; ongoing domestic conflict and international conflict, as well as the degree of militarisation. The GPI presents a data-driven analysis of trends in peace, its economic value, and how to develop peaceful societies. The Index covers 99.7 percent of the world’s population, using 23 qualitative and quantitative indicators from highly respected sources.

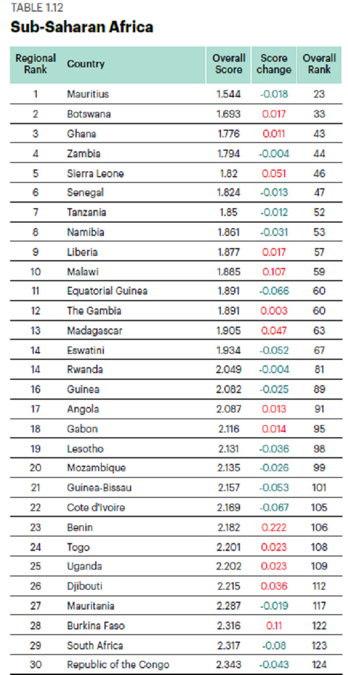

Overall, the index ranked Ghana as the 43rd against 44th last year in the world in its 14th edition. Ghana moved one place from the 2019 GPI and is now behind only Mauritius (1st) and Botswana (2nd) in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the Index, Ghana’s rise in the rankings was despite Sub-Saharan Africa recording a slight drop in peacefulness on the 2020 GPI, with an overall score deterioration of 0.5 percent.

Meanwhile, South Sudan remains the least peaceful country in sub-Saharan Africa. And that is quite expected given the internecine civil and ethnic war that has engulfed the oil rich country. South Sudan is one clear case of the proverbial ‘resource curse’, where instead of oil helping to alleviate poverty, is rather the source of the conflict and backwardness. As stated earlier, Ghana’s ranking once more came at the time we are heading for a general election, in which the main bone of contention is not who would win the election, but who qualifies to cast a vote to elect the president or a member of parliament.

Overall, 20 countries in the region improved in peacefulness while 24 deteriorated. The region’s three largest improvers in peacefulness in the last year were South Africa, Cote d’Ivoire, and Equatorial Guinea, all of which recorded improvements of more than six percent. Sadly, Benin experienced the biggest deterioration of any country in the world, falling 34 places in the ranking to 106th on the 2020 GPI.

Global

The global scene has not changed much. Iceland remains the most peaceful country in the world in 2019, as in 2020; a position it has held since 2008. It is joined at the top of the index by New Zealand, Austria, Portugal, and Denmark. Afghanistan is the least peaceful country in the world for the second year in a row, followed by Syria, Iraq, South Sudan and Yemen. All, except Yemen, have been ranked amongst the five least peaceful since at least 2015. The lessons GPI teaches all of us, the rulers and the ruled is that the rule of law and respect for due process promote economic growth.

Rule of law

With election 2020 just six months away, all state institutions must become proactive in sustaining Ghana’s global outlook as a peaceful country. In fact, is fast becoming Africa’s best-case study for democracy and democratization. When U.S.A. President, Barack Obama visited Ghana after the nail-biting 2008 elections, he reminded Ghanaians and Africans that democracy did not need strong men, rather, it needs strong institutions. In modern times, democracy has been equated to elections or “a system of government in which all the people of a state or polity….elect representatives to a parliament or the presidency. Democracy is further defined as (a:) “government by the people; especially : rule of the majority (b:) “a government in which the supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them directly or indirectly through a system of representation ….”[

For democracy, peace and stability to prevail, the rule of law must be upheld as number one ground rule. The rule of law is the legal principle that law should govern a nation, as opposed to being governed by arbitrary decisions of individual, pressure groups and government functionaries. It primarily refers to the influence and authority of law within society, particularly as a constraint upon behaviour, including the behaviour of a current president or a past president. Therefore, any actions taken outside the law are ultra vires and against the spirit and letter of the 1992 Constitution.

NDC and EC

In May 2020, one Takyi-Banson, a private citizen sued the Electoral Commission for embarking on its Constitutional mandate to compile a new voter register. He was joined by the opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC). The bone of contention was that EC had no right to exclude holders of the previous voter ID as a form identity to register. NDC sought a number of relieves, the first being that the attempt by the EC to compile a new register was unconstitutional, and second that the decision of the EC to exclude an existing voter ID as a form of identification for the exercise was also unconstitutional. The Supreme Court’s assessment of the two cases was that NDC should prioritise one of the cases for hearing to begin. NDC opted for the relief-that the Supreme Court should compel the EC to accept previous cards issued by the EC as a form of identity. The road was now clear for the final ruling.

Amicus Curiae

Before the ruling on June 23, the Apex Court dismissed an application filed by think tank, IMANI Africa and other civil society organisations, to be a friend of the court in the in the case between NDC and EC. IMANI had filed an Amicus Curiae to assist the Supreme Court through offering information, expertise or insight that had a bearing on the issues in the case. Amicus curiae is one who assists the court by furnishing information or advice regarding questions of law or fact. He/she is not a party to a lawsuit and thus differs from an intervenor who has a direct interest in the outcome of the lawsuit.

For months, IMANI and 17 civil society organisations had argued against the compilation of a new register, insisting that it would not be value for money. The CSOs argued that the biometric verification machines had continually been improved since 2016, with the EC spending more than $60 million in updating the verification machines. Counsel for the CSOs and IMANI, Joe Aboagye Debrah, argued that his clients were well known and had played an important role in the governance of the country. “My lord, we are bringing relevant information to help the court. We are not only restating information which is already there but additional information”, he pleaded.

NDC and the CSOs held that the exclusion of the existing voter ID card would disenfranchise millions of Ghanaians and deny them the right to vote.

However, the Attorney General countered that the CSOs would not add anything to the case; hence their application should be thrown out. The Deputy Attorney-General, Godfred Odame, said the application was supposed to bring some important information but that was not the case. Subsequently, the Supreme Court unanimously dismissed the IMANI case, affirming that it had no place in law. It is worthy of note that in his delivery the Deputy Attorney General presented evidence from the National Identification Authority, the Passport Office and Ghana Statistical Service to justify that without the use of old voter register eligible voters could still register and vote. Surprisingly, the NDC legal team present little, if any evidence to the court. At best they presented their case with emotions or simple, they “tried to appeal to emotions”. And in court, emotions have little impact on outcomes of cases, especially in constitutional cases. The response of the NDC to the Supreme Court’s ruling was meant to cause chaos ahead of the commencement of registration on June 30. The General Secretary of the NDC convincingly indicated that the Supreme Court had given the green light that the old ID cards should be used to register. In fact, the Supreme Court did not say so. Then the former President, John Mahama’s comment that the Supreme Court ruling gave the EC ‘the leeway’ to do what it wants, was also unfortunate and deplorable. Such comments can only sow seeds of discords ahead of the December 7 polls and after. As I stated earlier, the rule of law should be the number one ground rule for democracy; so, all interest and pressure groups must play by the rules.

Role of NGOs and CSOs

The role of NGOs and CSOs in the democratization process across the world has well documented. In fact, so central have NGOs and CSOs become in the new agenda to promote democracy in Africa that, donor agencies invested a lot of money in promoting their capacity to contest and question state policy. Civil society were empowered to stimulate ‘social capital’ as part of the changing international development policy landscape. Despite this critical role of CSOs in the changing policy landscape, some donors have begun to express worry about some negative implications of the value orientation of some NGOs and CSOs. Their increasing and overly political nature undermine their credibility over time. This led donor agencies to start refocusing on building the capacities of ‘think tanks.’ But partisan nature of some think tanks are beginning to defeat the very purpose for taxpayers of donor countries continue to finance them.

References

Arblaster, A. (2001) “Democracy”, Open University, Milton Keynes

Potter, D. (1997) “Explaining Democratisation”, in Allen, T and Thomas, A. (eds.) Poverty and Development into the 21st Century, Oxford/Open.

(***The writer is a Development and Communications Management Specialist, and a Social Justice Advocate. All views expressed in this article are my personal views and do not represent those of any organization(s). (Email: [email protected]. Mobile: 0202642504/0243327586