Right now, we are being told that the novel coronavirus that causes the Covid-19 disease is such an existential threat to all of us that we need extreme measures to deal with it.

More than half the world’s population is bunkered down at home under effective house arrest; a form of medical martial law prevails of the streets; most “nonessential” shops and businesses are closed; and trust and social contact between people has almost completely broken down. So is the threat from the new disease worthy of these unprecedented consequences?

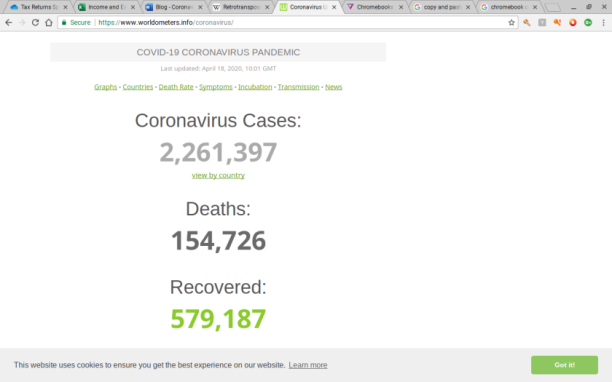

Let’s take a close look at the figures. A good source of official data which is updated regularly is the Worldometers Coronavirus page. The latest figures here as of the time of writing (25th April 2020) are shown by the following summary snapshot from the site:

So, at this time we have more than two and a quarter million cases and more than 150,000 deaths. That sounds pretty bad, right? But we can only put this into context if we compare with the numbers for deaths and cases from other, broadly similar diseases and, for deaths, by comparing with global death rates as a whole. I will return to the subject of death rates later, but firstly let’s concentrate on case numbers: how are these numbers being calculated? We hear a lot about testing of suspected cases, but what do we know about these tests.

The first thing to note is that, perhaps contrary to popular belief, there is not one standard test being used around the world to test for coronavirus infection; each country is more or less using its own methodology.

Also, as I have discussed in a previous post, tests are not a magic 100% reliable indicator of whether someone has a disease or not. Some of them are really quite unreliable indeed. It’s actually quite a technical challenge to make accurate tests for common diseases, particular those caused by viruses.

If it were that easy, the shops would be full of such test kits. Do you not think there would be a huge market for a simple, accurate home test for, say, the flu? And the market would undoubtedly be much bigger for home tests for embarrassing viral diseases such as herpes and sexually transmitted infections.

And even if it were possible to manufacture a fairly accurate test for a disease, if the disease you are testing for is uncommon (as is currently the case with Covid-19 despite all the media hype to the contrary) then the rate of false positives this test will give you will be really high. I will go into more detail on this later to illustrate that the world is largely suffering from a pandemic of false positives for Covid-19 rather than of the disease itself.

The general approach to testing for Covid-19 can be gauged from the US Centre for Disease Control’s (CDC’s) web pages on testing and their information for laboratories doing Covid-19 testing. So, let’s take a look at the two main types of testing that are being done for Covid-19 around the world right now: polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based tests and serology/antibody-based tests.

PCR Based Tests

Many SARS-CoV-2 tests are based on what is called “Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction” or RT-PCR. This is a type of more general process called the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Wikipedia gives good general explanations of the principles of PCR testing as a whole, as well as the type of RT-PCR tests used for Covid-19 testing.

Without going into too many technical details here, the general idea of a PCR test is to take a sample from a patient and multiply up all the target DNA in the sample (using the polymerase chain reaction, PCR). The target DNA sequence used is designed to try and uniquely identify the target virus or bacteria so that if this sequence is found you can be reasonably sure you have found the target organism.

Serology/Antibody Based Tests

Given all the problems with PCR based testing, some companies and countries are investigating the use of antibody-based tests instead. The idea here is to try and detect antibodies – proteins produced by the body to fight infection – against the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the blood or other bodily fluids of a patient. The UK is working on getting antibody tests available in bulk for their population. The CDC in the US is also looking at developing such tests.

I won’t discuss these kinds of tests in so much detail because most countries including our own Ghana and health care systems are still mainly reliant on RT-PCR based testing. This is partly because accurate antibody tests are not widely available, being both difficult and time consuming to prepare in great numbers. But suffice to say that antibody tests, even when they have been successfully manufactured, are also subject to many problems too.