Insights from the African Economic Outlook report for 2020[1] indicate that although the economy of Africa grew at 3.4% in 2019, North Africa accounted for the largest economic output, contributing 44% of economic growth in Africa – the high level of economic growth in the region is mainly attributed to a proliferation of oil revenue. North Africa hasrecorded decelerations in economic growth in the last quarter of 2010, as oil revenue declined when oil production was interrupted by the Arab Spring[2]. But, higher levels of production beyond expectation and export of oil in Libya which resulted in 55.1% growth in GDP stimulated economic growth in North Africa after 2016[3]. Oil revenue is the primary driver of economic growth in North Africa and other net oil-exporting countries on the continent – according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy report for 2019[4], Africa accounts for 7.2% of global oil reserves. In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where the largest oil exporter (Nigeria) and the largest oil importer (South Africa) are located, oil-exporting countries account for close to 50% of GDP growth in the area[5].

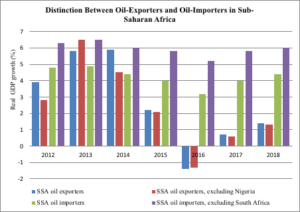

Oil-exporting countries in SSA rely heavily on revenues harnessed from oil, a condition that has a ripple effect on the development[6] of the region – the decline in GDP growth in SSA from 5.1% to 1.4% in 2014 and 2016, respectively, was due to oil price shocks, when the price of crude oil fell by 56% within a seven-month period. In 2017, whiles economic growth in oil-importing countries was 4%, oil-exporting countries experienced a growth of less than 1%, depicting the disparity between the two groups on the subcontinent[7]

Source: International Monetary Fund & Citibank

Highlights from the International Energy Agency report for 2019 shows that 11 countries in SSA contribute three-quarters, two-thirds and three-quarters of the region’s GDP, population and energy demand, respectively – these countries include Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Kenya, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Senegal, Tanzania, Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola and Côte d’Ivoire.

Even though Africa’s abundant oil and gas resources serves as an essential source of revenue, generating $1.7 trillion in net income to African producers during the commodity boom in the 2000s, the contribution of oil revenue to oil-exporting countries is indispensable – accounting for 90% of fiscal revenue in SSA[8]. With 7.1% of global gas reserves, natural gas does not have a great impact in energy development outside North Africa – natural gas accounts for only 5% of the energy mix in SSA, one of the lowest in the world[9].Colossal depreciation of global oil and gas prices between 2014 and 2016 diminished net income from the two commodities among producers and exporters in Africa. This created a huge revenue gap for governments of oil-exporting countries which consequently had a negative effect on economic growth.

Source: International Energy Agency

The shrinking of oil revenue with close to 50% drop in the price of the commodity prompted several oil-exporters such as Nigeria, Africa’s largest oil producer, to revise National budgets for 2015 by reducing spending, particularly capital expenditure – with oil being a major source of foreign reserve, a dwindle in the price of the commodity decreases oil revenue and also accounts for the depreciation of local currencies against the US dollar.

A condition which compelled the central bank of Nigeria to increase policy rate and also conserve foreign reserves in an attempt to protect the Nigerian Naira in 2015 – the Naira depreciated by more than 20% between 2014 and 2015 as inflation increased in the first half of 2015. However, the relationship between oil price fluctuations and exchange rate in Nigeria and South Africa, the two largest economies in Africa, seems to be similar. In spite of the fact that Nigeria is the largest oil-exporting country and South Africa is also the largest oil importing country in Africa, recent research suggests that an increase in oil prices lead to a depreciation of both the South African rand[10]and the Nigerian Naira[11] vis‐à‐vis the United States dollar – currency depreciation is one variant of the resource curse most resource abundant developing economies experience from time to time.

In Angola, the second largest oil producer in Africa[12], similar precautionary measures were applied as was carried out in Nigeria – the Angolan Kwanza devalued after the central bank increased the policy rate. On the other hand, in oil-importing African countries, the fall in the price of oil reduced inflation – this aided central bank in oil-importing countries such as South Africa and Kenya to steadily maintain interest rates[13]. Highlights from the World Economic Situation and Prospects report for 2020, shows that although GDP growth for the economy of Africa is projected to be 3.2% and 3.5% in 2020 and 2021, respectively, the lingering effect of global oil price shocks has a greater impact on economic growth on the continent[14].

Despite the extreme importance of oil to African economies, the production and usage of the commodity is a major source of greenhouse gases – according to the United States Environmental Agency, burning of fossil fuel for electricity, transportation and heat constitute the largest source of greenhouse emissions[15]. These emissions deplete the ozone layer and make the earth warmer – according to the United Nations Environmental Programme[16] Africa will suffer the most from climate change partly because of the continents geographical position.

Yield from rain-fed agriculture can be reduced by 50% with more than half of the region’s population being at risk of undernourishment if global warming reaches 2˚C. Unlike other parts of the world, specifically the developed countries, Africa, emits comparatively less greenhouse gases yet the continent is exposed the most to adverse effects of climate change – a report from the International Energy Agency asserts that between 1890 and 2018, energy-related carbon dioxide emissions in Africa represent 2% of global cumulative emissions[17].

Source: International Energy Agency

The complexity of climate change-economic growth nexus is evident in extant research – a working paper of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)[18]shows there is a large negative effect of higher temperatures on economic growth in poor countries. The study further reveals that in poor countries, a 1°C increase in temperature in a year reduces economic growth by 1.1 percentage points within the period, ceteris paribus. Another study also affirms that a percentage increase in temperature reduces the economic performance of countries in SSA by 0.13%, all other factors held constant – agriculture accounts for 23% of GDP and employs 60% of the population in SSA making the region vulnerable to the pernicious effects of climate change especially as rain-fed agriculture is widely practiced with only 7% of the total cultivated area of 183 million hectares use irrigation on farmlands[19].

Even though the African continent has appreciable oil and gas reserves, a large proportion of the region’s population specifically the rural population in SSA cannot access energy resources; apparently 600 million Africans have no access to electricity, while 780 million rely on traditional solid biomass for cooking. Although Africa has a significant quantity of energy resources such as hydropower, sunshine, geothermal and wind, the continent accounts for less than 1% of global investment in renewable energy – to accelerate the usage of renewable energy, Africa will require $1 trillion investment in the energy sector in the next 20 years in order to meet the energy demand. The World Bank suggests infrastructure development in the energy sector will cost $43 billion annually[20].

As pointed out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the use of fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas release huge amount of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, which eventually causes global temperature to rise. In as much as revenue from oil resources foster economic growth, the extraction and usage of the commodity damages the environment[21].

About the Authors

Alexander Ayertey Odonkor is a chartered financial analyst and a chartered economist with a stellar expertise in the financial services industry in developing economies. Alexander has completed the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) program on Financial Programming and Policies – with a master’s degree in finance and a bachelor’s degree in economics and finance, he also holds a postgraduate certificate in mining from Curtin University. His research works have been published by the Global Business Review, International Journal of Economic Development etc.

Dr. Paiman Ahmad is an academic with research interest in oil price politics, energy governance, rentier economies and sustainable development in developing economies. She holds a master’s degree in International Affairs and Public Policy Making (Bilkent University-Ankara) and a PhD in public administration from National University of Public Service. Her research works have been published by reputable journals such as Public Money & Management, Journal of Public Affairs and top-tier academic publishers: Palgrave Macmillan, Springer, Routledge, Wiley and many others. Her Academic Affiliations are: University of Raparin, Lecturer in Law and Administration Departments.

Emails:[email protected]. [email protected]. Rania-Sulaimania-Kurdistan Region-Iraq. Visiting lecturer at Tishk International University: International Relations & Diplomacy Department, Faculty of Administrative Sciences & Economics, Kirkuk Road, Erbil- Kurdistan Region -Iraq. Email: [email protected].

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.hu/citations?user=88EszakAAAAJ&hl=en

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Paiman_Ahmad

ORCID iDhttps://orcid.org/0000-0002-5887-3782

References

[1]African Development Bank Group ‘‘African Economic Outlook 2020: Developing Africa’s Workforce’’ Available at: https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/african-economic-outlook-2020 (Accessed: 25 May, 2020).

[2]World Bank (2012) ‘‘Middle East and North Africa Economic Developments and Prospects, October 2012: Looking Ahead After a Year in Transition’’. Middle East and North Africa Economic Developments and Prospects. Washington, DC. United States. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11979 (Accessed: 26 May, 2020).

[3]African Development Bank Group ‘‘North Africa Economic Outlook 2018’’ Available at: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/2018AEO/African-Economic-Outlook-2018-North-Africa.pdf (Accessed: 19 May, 2020).

[4]BP ‘‘BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019’’, 68th Edition. London, UK. Available at:https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2019-full-report.pdf (Accessed: 26 May, 2020).

[5]World Bank (2015) ‘‘Global Economic Prospects: Having fiscal Space and Using it’’ 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433, United States. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/GEP/GEP2015a/pdfs/GEP15a_web_full.pdf (Accessed: 26 May, 2020).

[6] Coulibaly, B. S. & Madden, P. (2020) ‘‘Strategies for coping with the health and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa’’ Brookings Institution, 18 March [Online]. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2020/03/18/strategies-for-coping-with-the-health-and-economic-effects-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-africa/ (Accessed: 19, 2020).

[7] Gursel, G. (2018) ‘‘Africa Corporate Treasury – Who is your Catalyst for Innovation?’’ Citibank. Available at: https://www.citibank.com/tts/insights/articles/article13.html (Accessed: 27 May, 2020).

[8]World Bank (2015) ‘‘Global Economic Prospects: Having fiscal Space and Using it’’ 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433, United States. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/GEP/GEP2015a/pdfs/GEP15a_web_full.pdf (Accessed: 27 May, 2020).

[9]BP ‘‘BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2018’’, 67th Edition. London, UK. Available at:https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2018-full-report.pdf (Accessed: 27 May, 2020).

[10]Fowowe, B. (2014) ‘‘Modelling the oil price–exchange rate nexus for South Africa’’, International Economics, Volume 140, Pages 36-48, ISSN 2110-7017,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2014.06.002.

[11] Muhammad, Z., Suleiman H. & Kouhy, R. (2012) ‘‘Exploring oil price—exchange rate nexus for Nigeria’’ OPEC Energy Review, 36, 383–395. doi:10.1111/j.1753-0237.2012.00219.

[12] Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (2019) ‘‘Angola facts and figures’’ Available at: https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/147.htm (Accessed: 28 May, 2020).

[13] Kambou, G. (2015) ‘‘The impact of low oil prices in Sub-Saharan Africa’’ World Bank, 28 August [Online]. Available at:https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/impact-low-oil-prices-sub-saharan-africa (Accessed: 28 May, 2020).

[14] United Nations (2020) ‘‘World Economic Condition and Prospects’’ New York, United States.Availableat: https://unctad.org/en/pages/PublicationWebflyer.aspx?publicationid=2619 (Accessed: 28 May, 2020).

[15]United States Environmental Agency ‘‘Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions’’ Available at: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions (Accessed:28 May, 2020).

[16] United Nations Environmental Programme ‘‘Responding to Climate Change’’ Available at: https://www.unenvironment.org/regions/africa/regional-initiatives/responding-climate-change (Accessed: 28 May, 2020).

[17] International Energy Agency ‘‘Africa Energy Outlook 2019’’ Available at: https://webstore.iea.org/download/direct/2892?fileName=Africa_Energy_Outlook_2019.pdf (Accessed: 28 May, 2020).

[18] Dell, M., Jones, B.F & Olken, B.A (2008) ‘’Climate Change and Economic Growth: Evidence from the Last Half Century’’ National Bureau of Economic Research. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w14132.pdf (Accessed: 28 May, 2020).

[19] Goedde, L., Ooko-Ombaka, A & Pais, G (2019) ‘‘Winning in Africa’s agricultural market’’ McKinsey Global Institute, 15 February [Online]. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/agriculture/our-insights/winning-in-africas-agricultural-market (Accessed: 28 May, 2020).

[20] Coetzer, J & Vassan, S (2018) ‘‘Renewable Energy in Africa in the Era of Climate Change’’ White & Case, 27 September [Online]. Available at: https://www.whitecase.com/publications/insight/renewable-energy-africa-era-climate-change (Accessed: 03 June, 2020).

[21] Fleshman, M. (2007) ‘‘Climate change: Africa gets ready’’ Africa Renewal, United Nations [Online]. Available at: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/july-2007/climate-change-africa-gets-ready (Accessed: 03 May, 2020).