A director according to the UK and South Africa’s Companies Acts, Dodd-Frank, King IV and Sarbanes-Oxley Reports is a person who by any title undertakes that role by offering relevant directional input and guidance.

The Institute of Directors Ghana, best practice guide (pp.27) states that a director is “any person occupying the position of a director by whatever designated, and includes persons in accordance with whose instructions the directors of the company are accustomed to. They could be duly known as a council member, trustee or a governor.”

Ghana’s Companies Act 992 (2019 pp. 132) specifically defines directors as “persons by whatever name called, who are appointed to direct and administer the business of the company”. The Act further stipulates that a person who is described as a director of a company, whether the description is qualified by the word “local”, “special” “executive” or in any other way, shall be deemed to be held out as a director of that company.

In most jurisdictions, it is important to note that a person using the title of a director and not duly authorised as per the local Companies Act has no power or authority to represent shareholders.

Put simply, directors are part of the leadership of an organisation entrusted by law with certain powers relating to management and administration. They are elected by the shareholders to make important company policy decisions. Their overall purpose according to Hiagh J. is to “ensure the company’s prosperity by objectively directing the affairs to make certain that the interests of the shareholders and stakeholders are realised……”

Directors as affirmed by Fisher E. Kaler J, the Cadbury, Dodd-Frank, King IV and Sarbanes-Oxley Reports are also expected to oversee and resolve organisational challenges and socially responsible citizenry matters. Today, director actions may have significant implications for shareholder, employees, creditors and communities. Hence the need to have the right professional and competent persons on board.

Based on over 25 years of experience, and as a member the Institute of Directors-UK, the world’s oldest and foremost directorship body, a director is a professional who agrees to comply with governance principles, ethics and accept commitment to selflessness, integrity, competence, probity, and the promotion of the public good. Today, most professional directors are part of a recognised professional body such as the Institute of Directors. As professionals, directors are as rightly pointed out by Roe M. and Bebchuk L. essential and leading players in ensuring effective corporate governance “within and beyond” an organisation.

In her book, “In Boards We Trust”, Brenda Hanlon notes that directors are responsible to:

Provide continuity for the organisation by setting up a corporation or legal existence, and to represent the organisation’s point of view through interpretation of its products and services, and advocacy for them;

Select and appoint a chief executive to whom responsibility for the administration of the organisation is delegated, including: – to review and evaluate his/her performance regularly on the basis of a specific job description, including executive relations with the board, leadership in the organization, in product/service/program planning and implementation, and in management of the organization and its personnel; and to offer administrative guidance and determine whether to retain or dismiss the executive;

Govern the organisation by broad policies and objectives, formulated and agreed upon by the chief executive and employees, including to assign priorities and ensure the organisation’s capacity to carry out products/services/programs by continually reviewing its work;

Acquire sufficient resources for the organisation’s operations and to finance the products/services/programs adequately;

Account to the stockholders (in the case of a for-profit) or public (in the case of a non-profit) for the products and services of the organization and expenditures of its funds, including: – to provide for fiscal accountability, approve the budget, and formulate policies related to contracts from public or private resources; and to accept responsibility for all conditions and policies attached to new, innovative, or experimental products/services/programs.

Adding to this, Deloitte insist that a “director must exercise his or her powers and perform his or her functions: in good faith and for a proper purpose, in the best interest of the company, [and] with the degree of care, skill and diligence that may reasonably be expected of a person carrying out the same functions and having the general knowledge, skill and experience of that particular director.”

“Directorships and managerialships” are technically and legally different. Directors mostly direct and oversee whilst managers generally manage and operate.

Although these roles in terms of liabilities do overlap especially in relatively smaller organisations, it is critically important to note that directors in a number of instances perform dual roles: one as a joint and equal member of a board and the other as an executive director and head of a function, for example marketing, supply chain management, finance and operations.

Unless otherwise categorically stated in the articles of association, each director on the board has one vote and all decisions are made by a simple majority. This is regardless of executive or non-executive status.

The executive director versus the non-executive Director

According to King M, Wixley T, Keay A, the executive director is normally an employee of the company and involved in the day-to-day management and administration of the organization.

An executive director: typically reports directly to the board. In some instances, they are not part of the board and is invited to attend meeting to provide an update plus defend actions. The most common executive directors are the Managing Directors or the Chief Executive Officers of public and private companies.

They are responsible for carrying out directives from the board. Although executive directors are also involved in the day-to-day management of the organization, their duties may be shared with other executive directors. King M. amongst others, has consistently urged the need for “executive directors to strike a balance between their management of the company, and their fiduciary duties and concomitant independent state of mind required when serving on the board”.

A non-executive director: be it in private or private organisations is more of a part time role but brings with it, external independent support and guidance to the business. They have legal responsibilities similar to that of executive directors. Hence these days, they can equally be charged with negligence. It is for this reason why they are also expected to have a degree of detachment, objectivity and independence when fulfilling their fiduciary responsibilities.

Not being involved in the management of the company according to Deliotte defines “the director as non-executive. Such appointed professionals are independent of management on all issues including strategy, performance, sustainability, resources, transformation, diversity, employment equity, standards of conduct and evaluation of performance.”

Non-executive directors attend board meetings and where necessary meetings of sub committees. In most cases, these appointed experts spend less than 3 three days a month within the appointing organization.

Other types of non-executive directorships include:

Independent Director: They are non-executive directors who help the company to improve corporate credibility and enhance the governance standards. As an independent non-executive director, the individual is expected not to have a relationship with the company which might influence the independence of judgment. Very often such an individual could duly perform the role of the deputy chair and also chair various committees of the board. Independent non-executive directors are generally rare in privately and state owned organisations.

Shadow directors: Such persons are not appointed to the Board, but on whose directions the Board is accustomed to act. They are as equally liable as a director of the company, unless he or she is giving advice in his or her professional capacity.

Nominee directors: Such persons are appointed by certain shareholders, third parties through contracts, lending public financial institutions or banks, or by the Government in case of oppression or mismanagement. It is important that nominee directors are aware of conflicts of interests they have toward the company and the loyalties they hold in relation their nominators.

Alternate directors: Such persons are appointed by the Board, to fill in for a director who might be absent a period. Appointing an alternate director is the most useful way that directors can fulfil their duties and responsibilities if they know they will be absent for one or more board meetings, for example due to illness, jury duty, long holiday. At law, and according to the Institute of directors, alternate directors have the same rights, powers, duties and responsibilities as other directors. An alternate director can only be appointed with the agreement of a majority of the directors.

Professional directors: Such persons are appointed because of their unique expertise and qualifications and have no interest in the company.

A de facto director: Such a person has not been formally or properly appointed as a director, but nonetheless acts as a director.

A lead director: Such a person is a non-executive director, and preferably an independent director, who undertakes some of the roles of the chair which the chair is unable to perform possibly because they are an executive of the company. Appointing a lead director allows more independent oversight and assessment of the CEO and senior executives.

In appointing directors, King M, Cadbury, Sarbanes Oxley amongst others all advocate that a board made up of executive and non-executive directors, should preferably have a majority of non-executive directors who are independent of management. This will ensure objectivity in decision making, appropriate balance of power and authority on the board.

Being a director today comes with consequences for the person involved. They include a potential jail sentence or a heavy fine for negligence and destroying shareholder value. It is therefore critical that the individual considering a board role carefully weigh the implications of the appointment before taken the leap. The key to helping to reach a satisfactory conclusion is a proper due diligence and common sense applied during the process of accepting a board seat.

To be prepared as rightly pointed out by Light, D, King M, and Shultz S, is for directors

to be fully aware of the issues directly and indirectly affecting the company and ready to duly exercise their duties- the duty of loyalty, the duty of care and duty of independence.

To sum up, firstly the pressure is building on public, private and state owned entity board of directors to improve their oversight service delivery quality. This is dependent on the calibre of persons giving directional and supervisory inputs.

Secondly, in law, there is no real distinction between the different types of directors. Thus, all directors are required to comply with the relevant provisions, and meet the required standard of conduct when performing their functions and duties or face the dire consequences including, public disgrace, a heavy fine or a jail term.

Thirdly, before agreeing to become a director, it’s now very important according to Deliotte to do some research about the company, its board (if it currently has one), and the owner”. They further stress the need to “learn about the company’s financial situation, its business situation, and the key issues the company and the board are focused on before accepting to be or not to be a director of the organisation.

Finally, contrary to popular beliefs, a directorship is a profession requiring the highest level of professional competence. It is for this reason why practicing professional directors are increasingly being professionalised to have thought leading knowledge and skills derived from relevant research, education and practical experience to help them protect and grow shareholder and stakeholder interests and abide by their professional body’s code of ethics and conduct.

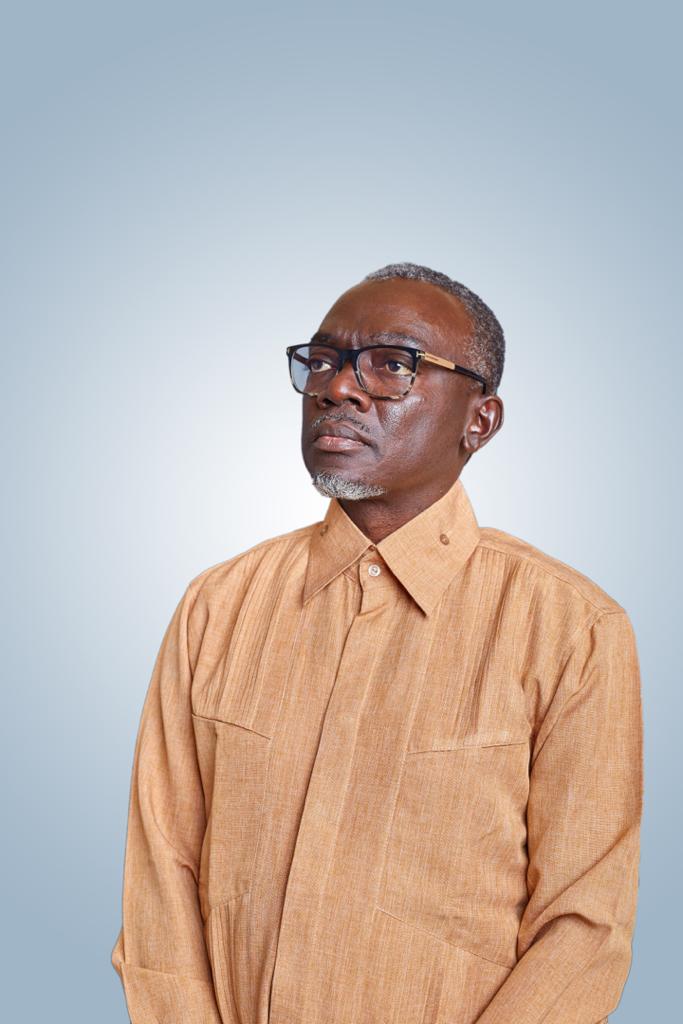

>>>the writer is an international chartered director and Africa’s first-ever appointed Professor Extraordinaire for Industrialisation and Supply Chain Governance. Independently recognised as one of the vertical specific global strategic thinkers on industrialization, supply and value chain governance and development, he continues to play leading academic and industrial roles in sectorial reforms both in Africa, and around the world. He is the CEO of PanAvest International and the founding non-executive chairman of MY-future YOUR-Future and OUR-Future (MYO) and the highly popular daily Nyansa Kasa series. For more information on COVID-19 updates and Nyansakasa visit www.myoglobal.org.